We have received many interesting questions and comments on our price stability mechanism since our official project announcement in May. In this post, we would like to shed more light on how Liquity keeps its stablecoin LUSD pegged to the USD. We will also look into the challenges faced by other stablecoins such as Dai which is currently struggling to keep its peg due to external influences.

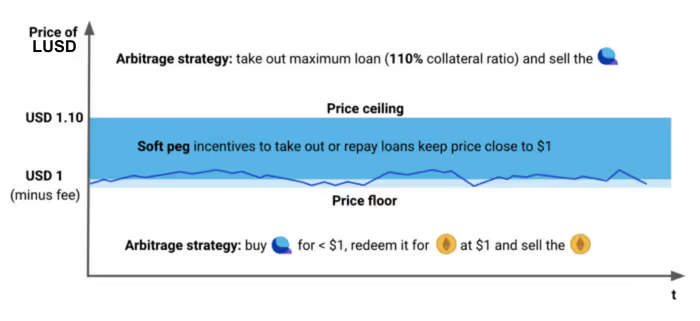

Various implicit and explicit mechanisms ensure that LUSD will closely follow the price of USD. We call mechanisms that are based on direct arbitrage opportunities “hard peg mechanisms” and call less direct processes “soft peg mechanisms”. In the following, we go through the different mechanisms one by one.

Hard peg mechanisms

Price floor at USD 1 (minus the applicable redemption fee)

One of the core innovations of Liquity is that its native stablecoin is redeemable against the underlying collateral held by the borrowers. That means, every LUSD holder can exchange their coins for Ether at face value, i.e. for 100 LUSD they would get USD 100 worth of Ether. When redeemed, the system uses the LUSD to repay the riskiest Trove(s) with the currently lowest collateral ratio, and transfers the respective amount of Ether from the affected positions to the redeemer. In other words, the Ether is drawn from the Troves’ collateral, starting from the position with the lowest collateral ratio.

To enhance user experience for low-collateral borrowers whose loans (Troves) may be vulnerable to redemptions, the system charges a one-off fee on every redemption, called the redemption fee. Being variable, this fee starts at 0%* and increases with every redemption, while decaying to 0% if no redemptions occur over time. The fee makes sure that redemptions will not be more frequent than necessary from a price stability perspective.

As a result of the redemption mechanism, speculators can make instant arbitrage gains whenever the Ether they get in return is worth more than the current value of the redeemed stablecoins. In other words, when the price of 1 LUSD is below 1 USD minus the redemption fee applied to 1 LUSD, they can immediately sell the redeemed Ether at a higher price than what they paid for LUSD in the first place.

Since the redeemed LUSD is burned by the protocol, the stablecoin supply (monetary base) will shrink upon every redemption, which usually has a positive effect on the price. As redemptions can be triggered automatically by bots whenever there is an arbitrage opportunity, we expect the exchange rate to quickly recover if it drops below the line.

It is important though to have the right formula for the redemption fee. If the fee is too high, redemptions may become prohibitively expensive even if the price of 1 LUSD is significantly below USD 1. In other words, if the redemption fee spikes due to a large redemption without an equivalent immediate reaction of the LUSD price, further redemptions may not be profitable until the fee comes down to a sufficiently low level again. On the other hand, if the fee is too low, there will be more or larger redemptions, increasing the risk for low-collateral borrowers of being hit by a redemption.

In our white paper, we propose to determine the redemption fee based on the following base rate formula:

b(t) := b(t-1) + 𝛼 * m/n

where b(t) is the base rate at time t, m the amount of redeemed LUSD, n the current supply of LUSD, and 𝛼 is a constant parameter. By modulating the fee resulting from a redemption, 𝛼 has an impact on the “hardness” of the price floor. To find the sweet spot, we have to make two assumptions:

- Arbitrageurs redeem their LUSD as soon as the peg falls below USD 1, and attempt to maximize their profit

- The Quantitative Theory of Money (QTM) holds: if the price of LUSD is below parity by k%, it takes a redemption of k% of the total LUSD supply to restore the peg

These assumptions allow us to derive the optimal value for 𝛼. It turns out (see this derivation) that by setting 𝛼 to 0.5, profit-maximizing arbitrageurs will redeem just as much LUSD as is needed to restore the peg based on the QTM.

Of course, this formula based on classical monetary theory does not guarantee that the exchange rate will always immediately return to parity. However, given the soft peg mechanisms described below, it is unlikely that such a situation will persist for longer periods of time.

If we just look at the hard price ceiling, the recovery speed will mainly depend on how fast the underlying base rate decays to 0%. The exact formula as well as the decay factor are still subject to research and will be determined based on extensive economic modelling.

Price ceiling at USD 1.10

Interestingly, the minimum collateral ratio of 110% creates a natural price ceiling at USD 1.10. When the LUSD:USD exchange rate exceeds that level, borrowers can make an instant profit by borrowing the maximum amount against their collateral and selling the LUSD on the market for more than USD 1.10. If 1 LUSD trades at USD 1.11 for example, you can lock up USD 110 worth of Ether, take out a loan of 100 LUSD and sell it for USD 111. No matter if your loans gets liquidated or not, you have made an arbitrage gain of 1 USD.

We expect that this arbitrage opportunity will steer LUSD away from reaching USD 1.10 and if it ever hits the ceiling, it will rebound very quickly. This should mitigate a mass influx of risky loans taken out at the minimum collateral ratio in such breakout situations.

The following figure summarizes the hard peg mechanisms:

Soft peg mechanisms

Parity as a Schelling point

Similarly to other collateralized debt platforms like MakerDAO, Liquity treats its stablecoin as being equal to USD when determining the collateral ratio of its Troves. Even though the borrower’s debt is denominated in LUSD, the current value of the Ether held as collateral is expressed in USD. Thus, the collateral ratio is defined as the collateral in USD divided by the debt in LUSD.

With this enshrined formula, parity between LUSD and the USD is fundamentally anchored in the system as its intended natural equilibrium state. Given the redemption mechanism, hard price floor and clear branding as a dollar-based stablecoin, we expect users to view the 1:1 dollar peg as a Schelling Point to which the system tends to return after temporary deviations.

As long as most people foster that belief, it will have a self-reinforcement effect: a LUSD price above $1 makes borrowing more attractive (as you can expect to repay at a rate of $1 or lower), whereas a price below $1 incentivizes repaying existing debts (as this state is likely to be short-lived). When more LUSD is borrowed than repaid over time, the total LUSD supply will grow, which should make the tokens cheaper with regard to the USD and other currencies. Conversely, if the repaid amounts are higher than the new debts, the money supply will shrink, such that LUSD will appreciate.

Generally, the long-term outlook of a 1:1 exchange rate between LUSD and USD will stabilize the price in the short run too since users will factor in future price changes in their current decisions (buy/sell/borrow/repay etc.). Given that this mechanism crucially depends on assumptions about the future, it only acts a soft peg and does not provide hard guarantees for price stability.

Dampened speculation against the price ceiling

As shown above, the floating range of LUSD is confined between USD 1 (minus fees) and USD 1.10. Speculating against those hard borders is difficult and hardly profitable. We posit that this will make LUSD less prone to adversarial speculation in general. Let’s assume that LUSD trades at USD 1.09 for example. It is clear that the upside for holders is realistically only 1 cent, while the downside is 9 cents. The closer the price gets to the price ceiling, the less interesting it becomes to speculate on further price increases.

Issuance fee for new debts

Existing systems such as MakerDAO apply variable interest rates (stability fees) as an additional soft peg mechanism. Liquity replaces interest rates by an algorithmically determined one-off issuance fee on debt.

The issuance fee constitutes an upfront cost that borrowers need to pay for the LUSD they draw. Similarly to the redemption fee, it is automatically increased upon every redemption (which signals that LUSD is likely worth less than the USD) and decays in phases without redemptions. Higher fees immediately make new loans less attractive, and thus throttle the generation of LUSD if there is not enough demand to keep up with the supply.

An increased issuance fee has a very direct effect on new debts compared to an interest rate increase which takes longer to impact supply. Existing loans are not directly affected by the issuance fee as such. However, if a loan gets closed due to a redemption, its owner might not be willing to reopen the position as long as the fee is high. This ensures that the LUSD burned upon redemptions is not recreated through new loans right away. The issuance fee and the redemption mechanism thus work in tandem to slow down the growth of the monetary base or contract it if needed.

Intuitively, the issuance fee should be in the same range or even be identical to the current redemption fee. The reason is this: If the redemption mechanism succeeds to push a lower price back to parity, new loans will become more attractive (see above “Parity as a Schelling Point”). If the QTM holds, the resulting base rate will roughly correspond to the difference in percentage points between parity and the previous price level. By charging the same base rate as an issuance fee, we can basically cancel out the attractiveness gain for loans due to the restored peg.

Effects of the price on leverage

Liquity and other collateral debt platforms enable decentralized leverage by converting the borrowed amount and using it as collateral for further loans. The maximum achievable leverage ratio mainly depends on the minimum collateral ratio MCR and can be determined by the following formula:

maximum leverage ratio = MCR /(MCR-100%)

While MakerDAO with its 150% minimum collateral ratio allows for a 3x leverage, Liquity’s maximum leverage ratio is 11x. Of course, these are theoretic maxima since in practice you need to maintain some security margin as a borrower.

Also, this formula is based on a stablecoin price of exactly 1 Dollar. If LUSD trades above parity, even higher leverage ratios become possible as the borrowed LUSD can be converted into more collateral:

maximum leverage ratio = (MCR/price)/(MCR/price-100%)

For a LUSD price of e.g. USD 1.05, the maximum leverage is 22x, or twice as high as during times with perfect price parity. In the case of MakerDAO, this is very different, since a Dai price of USD 1.05 will only slightly increase the maximum leverage from 3x to 3.333x, using the same formula.

People normally use leverage because they expect the collateral to appreciate by the time they close their position. However, an expectation of a depreciating debt can increase profitability as well. A higher LUSD price makes leverage more attractive, assuming that the position can be closed at a lower price in the future. It is therefore not only the higher leverage ratio, but this extra profit opportunity that should act as an additional incentive for leverage seekers whenever LUSD trades above parity.

But there is another effect that requires more explanation. At any given Ether price and even in sharp market downturns, we can expect that a certain (even if small) fraction of speculators will believe that LUSD will return to parity, making the leverage profitable. Such speculators can draw a multiple of their invested funds as fresh LUSD through leverage.

On the other hand, people who think LUSD will remain above the peg or even appreciate can only use their own funds to invest in LUSD. In other words, Liquity offers leverage solely for Ether but not for LUSD. Therefore, it only amplifies the supply side, but not the demand side when LUSD is overpriced. This process may help to push the price back to parity.

While the same mechanics are also present in MakerDAO, their effects are dwarfed by the 150% minimum collateral ratio. As we have seen, price appreciation has been a chronic issue for DAI. We think that Liquity has a much stronger soft peg mechanism that will pull the price down to parity when needed.

Stability Pool as a liquidity reserve

A certain fraction of the entire LUSD supply will be inside the Stability Pool and thus outside regular circulation. However, the pooled fraction of LUSD may depend on the current LUSD:USD exchange rate. The higher the price of LUSD in USD, the lower will be the (expected) collateral surplus gains in case of liquidations, since the conversion is based on the nominal value of LUSD being equal to USD.

As the price of LUSD approaches USD 1.10, the risk of a potential loss for depositors increases accordingly, and stability deposits become less attractive. Eventually, owners may withdraw their stability deposits if the loss risk becomes too high. With more liquidity being injected into the money markets by former stability depositors, the LUSD price should depreciate.

As a result, the Stability Pool will also act as a liquidity reserve and help to mitigate the liquidity crisis that might occur in case of black swan events affecting the Ether price. With that, the Stability Pool will serve both system stability (solvency) and price stability.

We think that this is a useful tradeoff despite the fact that it reduces the primary buffer for liquidations. Thankfully, the redistribution fallback mechanism and the Recovery Mode are designed to cope with mass liquidations even if the Stability Pool is emptied. While the redistribution of defaulted loans does not directly change the total collateral ratio of the system, it does reduce the individual collateral ratios of the borrowers who receive the debt and collateral shares, potentially below their respective comfort levels. Those borrowers may then either top up their collateral or reduce their debts in order to improve their collateral ratios, which in aggregate increases the total collateral ratio.

As an ultima ratio, the Recovery Mode changes the incentive structure for both borrowers and stability depositors. Only loans with a collateral ratio of 110% or higher at the time of liquidation are offset against the Stability Pool during Recovery Mode, while loans below 110% are directly redistributed to the other borrowers. This not only allows for higher collateral gains, but makes stability deposits practically risk free, assuming that the price of LUSD never exceeds USD 1.10.

Economic Modelling

We already mentioned that we are planning to do extensive modelling of our system. One of the questions we would like to answer is how price stability depends on the base rate, and what the optima parameters for the redemption and issuance fee formulas should be. We have already been talking to a few candidates that are experts in macroeconomic modelling and monetary economics.

It turns out that it probably makes sense to pursue our macroeconomic modelling separately from our agent-based simulations and stress testing. The latter are micro-focused, and explore how the behaviors of specific actors like arbitrageurs and speculators drive the system dynamics.

*Note that in the live version of Liquity borrow and redemption fees have been capped at a minimum of 0.5%